Graeme Johnston / 31 July 2023

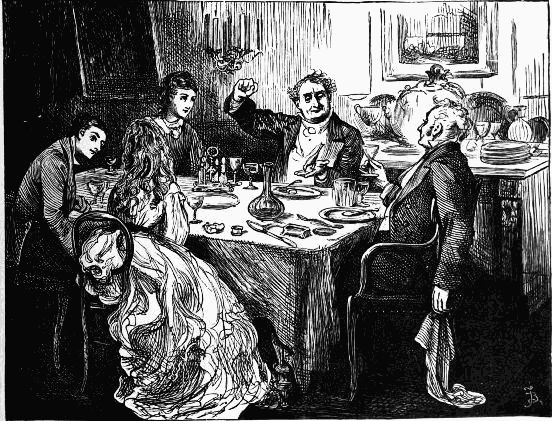

“By my soul, Jarndyce,” he said, very gently holding up a bit of bread to the canary to peck at, “if I were in your place I would seize every master in Chancery by the throat to-morrow morning and shake him until his money rolled out of his pockets and his bones rattled in his skin. I would have a settlement out of somebody, by fair means or by foul. If you would empower me to do it, I would do it for you with the greatest satisfaction!” (All this time the very small canary was eating out of his hand.)

“I thank you, Lawrence, but the suit is hardly at such a point at present,” returned Mr. Jarndyce, laughing, “that it would be greatly advanced even by the legal process of shaking the bench and the whole bar.”

“There never was such an infernal cauldron as that Chancery on the face of the earth!” said Mr. Boythorn. “Nothing but a mine below it on a busy day in term time, with all its records, rules, and precedents collected in it and every functionary belonging to it also, high and low, upward and downward, from its son the Accountant-General to its father the Devil, and the whole blown to atoms with ten thousand hundredweight of gunpowder, would reform it in the least!”

Charles Dickens, Bleak House (1853). Illustration by Frederick Barnard for an 1873 edition.

1. Introduction

Perennial problems of cost and delay have long led to searches for shortcuts in litigation which cannot be resolved by agreement.

This article summarises the current availability of such shortcuts in two neighbouring jurisdictions. One is England and Wales. The other is Scotland. The first is, of course, a common law system. The second is sometimes described as a hybrid system thanks to its mixture of home-grown concepts together with influences from continental Europe and south of the border.

I’m more comfortable in the common law: I first qualified and worked as a lawyer in England and Wales, and I’ve never qualified or worked as a lawyer in Scotland. But I live in Scotland these days and for various reasons I’m interested in the topic.

I’ve not spent a huge time bottoming out every detail, so there may well be errors: I would be glad to hear of any and will update the article with any that I find, or which are pointed out to me.

2. The attraction of shortcuts

A journey of a thousand miles begins with the words “I know a shortcut!” — Anon.

Let’s start by distinguishing two problems:

- Weak claims. Someone has sued you. The claim looks weak but the standard court process requires you to review and disclose documentary evidence, arrange witnesses, participate in a trial and engage in a lot of related processes. It’s going to involve huge expense, time, delay and stress. Surely there’s a way of getting to the point?

- Weak defences. You’re suing someone on a cut-and-dried basis. But they come up with an imaginative defence which threatens to bog the process down, with obvious risks as to your ability ever to recover what you are suing for. Again, the temptation is to look for a shortcut.

Judicial procedures in both parts of Great Britain have long responded to this problem. However, as we shall see, the solutions offered have been quite varied and their application has not proved straightforward. Pursuing a shortcut has often, when it’s failed, created further delay, expense or worse.

3. Demurrer, preliminary points of law and strike-outs in E&W

By the early 19th century, standard English civil court procedure involved written statements of the parties’ cases and responses (‘pleadings’), the gathering of evidence and a trial before a judge and jury. It all took a long time and cost a lot of money.

Courts allowed problem 1 (weak claims) to be addressed with a mechanism known as a demurrer. At that time, there were significantly different procedures for demurring between the courts of common law (e.g. King’s Bench, Common Pleas) and the court of chancery.

- In the common law courts, a demurrer involved admitting the facts alleged and arguing that they did not suffice in law to establish a claim. Such a process thus involved a huge risk for the defendant in anything but the most certain of cases. Lose on the legal point and the whole case was lost.

- In chancery, by contrast, a demurrer only involved assuming the facts alleged ‘for the sake of argument,’ enabling the point to be raised without as much risk. That said, the procedure was complicated and could be a source of significant delay and expense. Moreover, it only allowed challenges to be brought on the basis of legal objections.

A major programme of procedural experimentation and reform was undertaken in England from the 1830s. Following some initial missteps, a more sustainable path was followed from the 1850s and 1870s , culminating in the merger of the courts of common law and chancery into a single Supreme Court in the 1870s.*

* The term “Supreme Court” at that time encompassed the High Court and Court of Appeal. That terminology remained in effect until the 21st century. When the term “Supreme Court” was adopted to mean the final appellate court in 2009, the older “Supreme Court” terminology was changed to “Senior Courts.”

As part of that reform programme, the demurrer was finally abolished in 1883 and replaced by Order XXV of the new Rules of the Supreme Court, entitled ‘Proceedings in lieu of demurrer.’

- Rules (2) and (3) provided for parties to be able to raise points of law and have those disposed of by the court early on.

- Rule (4) empowered the court to strike out any pleading on the ground that it “discloses no reasonable cause of action or answer” – with power for the court then to enter judgment or stay the action.

- Rule (4) also empowered the court to strike out a case “shown by the pleadings” to be frivolous or vexatious – terms which have always been interpreted narrowly under English law.

4. Summary judgment in E&W

Two hundred years, at the outset of the industrial revolution, business people in England and Wales were unhappy about the delay and expense of obtaining judgment on commercial paper. John Bauman provides a detailed history in a 1956 article – the summary which follows is based in part on that.

In 1828, the prominent liberal politician, Henry Brougham, proposed in Parliament that a new procedure be introduced in English civil procedure for rapidly enforcing bills of exchange and other commercial paper, modelled on the existing Scottish procedure of “summary diligence.” That Scottish procedure allowed the holder of a bill or certain other commercial documents to register a claim in court following non-payment, with the registration being enforceable unless successfully challenged by the alleged debtor. The debtor was typically required to pay the claimed sum into court as a condition of being allowed to challenge the registration.

Before entering Parliament in 1810, Brougham had briefly been an advocate in Scotland (from 1800) and a barrister in England (from 1808) so was familiar with the difference between the two court systems. Scottish procedure in turn had been influenced by French and Dutch procedure, which provided for expedited judgment upon claims based on commercial paper.

Brougham’s proposal was that:

Whenever a strong presumption of right appears on the part of a plaintiff, the burden of disputing his claim should be thrown on the defendant. This I would extend to such cases as bills of exchange, bonds, mortgages, and other such securities. In those cases I think the plaintiff should be allowed to have his judgment, upon due notice given, unless good cause be, in the first instance, shown to the contrary, and security given to prosecute a suit for setting the instrument aside. This is a mode well known in the law of Scotland.

Brougham became Lord Chancellor two years later and was part of the reforming Grey government, whose legislative successes included the Reform Act 1832 and the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. However, reform of English civil procedure on Scottish lines proved too radical a step even for them. Or perhaps there were other priorities.

Brougham tried again quarter of a century later, in 1853, during the Aberdeen coalition ministry. The prospect of a Scottish registration procedure being adopted in English courts proved too much for Parliament, but a proposal from an English MP called Keating modified Brougham’s concept to be more in line with English notions of procedure. Keating’s version was enacted in 1855. Bauman summarises the effect thus:

Keating’s Act differed from the proposal of Lord Brougham in two important particulars: first, the English procedure, in avoiding the Scottish system of registration, postponed the entry of judgment until after the date set for the hearing of the motion; and second, Scottish summary diligence assumed that the creditor was entitled to execution against his debtor’s property unless the debtor suspended execution by furnishing security, whereas Keating’s Act required the posting of security as only one of several alternatives available to a defendant who asked leave to defend an action prior to the entry of judgment.

The procedure was then extended in stages. First, in the 1870s it was extended to all claims for debts or other liquidated sums. Then to actions to recover possession of land and goods, and to claims for specific performance of a contract to sell land. In the new Rules of the Supreme Court of 1883, the process was set out in Order XIV.

The details evolved over time. The 1883 procedure of requiring a special indorsement on the writ originating the process was relaxed. And in the 1930s, summary judgment was extended to all types of claim in the King’s Bench Division other than defamation, malicious prosecution, false imprisonment, fraud and a few others thought to be inherently unsuitable. Its extension was however limited by the low threshold which the defendant had to surmount: any plausible argument, even if improbable, would lead to summary judgment being denied.

In the late 1940s, another round of civil procedure reform was started, for the usual reasons. The group entrusted with it, chaired by Lord Evershed, reported in 1953. Given the limitations of summary judgment, they recommended an alternative procedure under which a “trial without pleadings” could be held in cases determinable on points of law or “construction” (i.e. interpretation) of a document.

This was originally implemented as Order XIV B of the Rules of the Supreme Court. A refined version introduced in 1990 as Order 14A empowered the court to “determine any question of law or construction of any document… where it appears to the Court that… such question is suitable for determination without a full trial of the action, and… such determination will finally determine (subject only to any possible appeal) the entire cause or matter or any claim or issue therein.”

I should also mention that similar provisions were also introduced into the County Court Rules (i.e. regional courts handling smaller cases). I don’t think discussion of the historical details of those would serve any useful purpose now that a single set of Rules (the CPR) applies to all kinds of court in England and Wales. However, one point worth mentioning is that it was the introduction of trial-without-jury in county courts in the 1840s which eventually prompted the removal, in stages, of jury trial from most civil cases in England and Wales. The few types of case in which it is still available (fraud, malicious prosecution and false imprisonment – and even there, rare in practice) are not the kinds of case in which summary judgment is likely to be relevant. As such, there is in practice hardly ever any question in England and Wales of a summary judgment application being pursued as a means of avoiding jury trial. The circumstances are significantly different to those in the United States.

5. The current E&W Civil Procedure Rules

In England and Wales in 1999, the previously separate Rules of the Supreme and Country Courts were replaced by a single set of Civil Procedure Rules.

These introduced new terminology, a new organisational scheme and some changes of substance. Relevant shortcuts include

- CPR Part 24 – summary judgment

- CPR rule 3.4(2) – strike-outs

- CPR rule 3.1(2)(i) – preliminary issues

5.1 Summary judgment under CPR

Rule 24.2 empowers the court to give summary judgment against either party (claimant or defendant) on the whole of a claim, or a particular issue, if it considers that

- the party has no real prospect of succeeding on the claim, defence or issue, and

- there is no other compelling reason to dispose of the matter at trial.

Rule 24.3 allows for this in any type of case except against the occupier in residential property possession claims (quite a contrast from the 19th century: repossession claims were one of the early categories of case in which summary judgment was permitted).

In cases where summary judgment is refused to a claimant, the court retains the discretion it has had since the 19th century to allow the defence to proceed unconditionally or, in ‘close call’ cases, to require the defendant to pay the disputed sum into court as a condition of being allowed to defend.

5.2 Striking out under CPR

CPR rule 3.4(2) provides that

The court may strike out a statement of case if it appears to the court –

(a) that the statement of case discloses no reasonable grounds for bringing or defending the claim;

(b) that the statement of case is an abuse of the court’s process or is otherwise likely to obstruct the just disposal of the proceedings; or

(c) that there has been a failure to comply with a rule, practice direction or court order.

Point (a) is modern language for the point we saw earlier in Order XXV(2) of the 1883 Rules. Its scope remains narrow, and these days it seems to be effectively superseded by the expanded concept of summary judgment.

Point (b) covers a variety of sins – mainly cases in which the claimant has acted dishonestly or with a blatantly improper purpose, or where the action is (in the old legal language) frivolous or vexatious. It includes cases of futility – where the remedy sought will be of no significant benefit to the claimant even if they win. The jargon for this last category is “Jameel abuse” after a leading Court of Appeal decision a few years after the CPR came into force. The court in that case emphasised the CPR concept of “proportionality” in extending the concept of abuse of process to such situations. There have been many attempts to apply it since, but the courts are generally reluctant to strike out other than in the most extreme cases.

5.3 What is the current test for summary disposal, exactly?

Sorting through the different formulations of the tests for summary judgment and strike-out for absence of reasonable grounds can sometimes feel a little like understanding the positions of the various factions in the Arian controversy.

Right at the outset of the CPR, in 2000, Jane Ching noted the contradiction inherent in Lord Woolf’s statement of intent:

I… propose that the test for summary judgment should be easier for applicants to satisfy than the current test… the new test will in fact give effect to the the corpus of judicial decisions on the current practice.

There was some real uncertainty at that time as to how it would be interpreted: would it represent a substantial change to the old practice, a major alternative to going to trial?

The language of subsequent judicial pronouncements does not help very much. In 2001, Lord Woolf himself, presiding in the Court of Appeal, that “real prospect of success” meant a case which was not merely fanciful, language which might seem to undermine the quotation above. Other early interpretations emphasised the need for a case with “some degree of conviction” – something that was more than just “arguable.” Court of Appeal judges also suggested early on that there was little practical difference between the tests under rules 24.2 (summary judgment) and rule 3.4(2)(a) (strike-out). Those early cases are conveniently summarised here by a District Judge writing in 2005, concluding that “the standard is higher than that which applied under order 14, although there is still scope for argument about how much better than ‘arguable’ a case must be. Watch this space.”

Later case law does not really clarify this, and the concept is inherently difficult to define anyway. Some mysteries remain, for example as to the application of the “other compelling reason” limb of rule 24.2, a point usefully discussed by Jane Ching back in 2000, and addressed in 2013 by Gordon Exall in the context of a case involving the business ventures of a reformed tax lawyer.

My impression is that a lot still depends on the exact circumstances, the skill of the lawyers and on the judge’s inclinations. In an extreme case, the court has gone so far as to give summary judgment to a claimant in a case of fraud – the 2021 Foglia case, usefully contextualised here. But, overall, such applications can still be highly unpredictable. Here is how Jonathan Lowe, an experienced barrister who started off as a solicitor, described his experience of its evolution in 2020:

Those of us who grew up pre-CPR had a staple diet of summary judgment applications (Order 14 of the RSC – Order 9, rule 14 of the CCR) – the test being simply: was there a “arguable defence”?… The replacement of the concept of “a real prospect” and “no other reason” why the case should proceed to trial have severely limited summary judgment to only the clearest possible cases of failed analysis, lack of evidence and lack of any cause of action. The latter case is more likely to be subject of attack under CPR 3.4 in any event. In large cases a summary judgment application may still succeed but inevitably will result in an appeal, multiply the costs spent and it will not lead to the intended result- a quick outcome to the litigation.

The fact that experienced practitioners can differ so much as to whether the post-1999 is more or less pro-summary disposal than the previous practice is perhaps indicative of the limitations of the concept.

5.4 Other procedures to bear in mind

- Preliminary issues. In addition to dealing with matters summarily (that is, without trial), the court has a discretion to order trial of a preliminary issue in any case. This may involve disclosure of documents and cross-examination of witnesses, all subject to the court’s case management powers to limit these. There must be some real benefit – such as resolving a significant part of the case and improving the prospects of settling the rest. Although I can’t find statistics, my impression is that such trials have become increasingly popular in the 21st century. Kate Traynor, a barrister, has published this useful 2022 detailed deck describing the courts’ expectations as to when a preliminary issue will be appropriate.

- Part 8 procedure. Another possibility under the CPR is to commence proceedings under Part 8. This is said to be designed for cases “unlikely to involve a substantial dispute of fact.” It is the new version of what was, before CPR, known as the originating summons procedure. While, on the face of it, this may sound as if it holds out the prospect of a simpler procedure, in practice it is restricted to certain types of specialist case, not general civil or commercial disputes.

- SLAPPs. In June 2023, the UK Government introduced a legislative proposal for the CPR to be amended to provide for easier dismissal of claims which are characterised as “strategic lawsuits against public participation,” defined quite narrowly as litigation to suppressing disclosure of economic crime and in which the claimant’s behaviour is intended to cause the defendant more expense or other harm than “ordinarily encountered in properly conducted litigation.” That’s obviously a very narrow definition indeed, arguably verging on the existing strike-out concept of abuse of process. But for present purposes the interesting point is that the onus is on the claimant to show that it is more likely than not to prevail at trial. A copy of the proposal is available here. The Government has indicated that this tentative reform is only a first step, and that it may wish to broaden its definition of SLAPPs in future. The main opposition party (Labour) has also indicated an intention to act in this area if it forms the next Government. It remains to be seen whether this shortcut will prove effective in practice. Note that these changes, if enacted, will only apply to England and Wales. Scottish civil procedure is devolved to the Scottish Government and it is unclear as yet whether it intends to do something to address SLAPPs.

6. Scottish civil procedure

Although I briefly touched on historical Scottish procedure above in discussing the history of summary judgment in England and Wales, I’m not going to attempt a historical survey of it in this article.

But the main shortcut possibilities today, as I understand them, are these.

6.1 Summary decree

First, summary decree is available to the party bringing a claim – known in Scottish procedure as the pursuer (equivalent to claimant in English procedure). The term “decree” is equivalent to the English term “judgment.” As in England, summary decree is not limited to specific types of claim. However, the Gill report on Scottish civil procedure in 2009 recommended that this be reformed by adopting the English CPR Part 24 approach in two respects.

The first was to extend it to both parties:

The current arrangements for summary disposal of court business are not even handed. A pursuer may apply for summary decree, but a defender who seeks dismissal of an action on the ground that it is clearly without merit must incur the cost and the delay of going to debate… There should be a procedure for summary disposal that is open to both pursuers and defenders, and that the court should be entitled to invoke itself.

The second was to relax the standard:

The test for summary decree to be granted is also too high… There should be a procedure for summary disposal that is open to both pursuers and defenders, and that the court should be entitled to invoke itself. The test should be that the pursuer or defender, as the case may be, has no real prospect of success and there is no other compelling reason why the case should not be disposed of at that stage.

Gill’s point about the test being ‘too high’ in Scotland may be illustrated by this quotation from the House of Lords’ decision a few years earlier, in Henderson v 3052775 Nova Scotia Limited [2003] UKHL 21:

The judge can grant summary decree if he is satisfied, first, that there is no issue raised by the defender which can be properly resolved only at proof and, secondly, that, on the facts which have been clarified in this way, the defender has no defence to all, or any part, of the action. In other words, before he grants summary decree, the judge has to be satisfied that, even if the defender succeeds in proving the substance of his defence as it has been clarified, his case must fail. So, if the judge can say no more than that the defender is unlikely to succeed at proof, summary decree will not be appropriate: it is only appropriate where the judge can properly be satisfied on the available material that the defender is bound to fail and so there is nothing of relevance to be decided in a proof.

That certainly appears a more summary-sceptical approach than that applicable south of the border. The 2009 Gill recommendation to adopt the English approach was implemented in the Sheriff Courts (analogous to the English County Courts) back in 2012 (see the two versions of Chapter 17 of the Sheriff Court Rules). It has not yet been implemented for the Court of Session (analogous to the English High Court) (see Chapter 21 of its rules), but a report in 2022 repeated the view that it should be (see para 2.49). I haven’t been able to identify whether the delay (14 years and counting since the Gill report) is reflective of some controversy on the topic within the judiciary or simply a result of inertia (any insights would be welcome).

6.2 Debate

Second, while strike-outs are not a thing in Scotland, the court has power to do something similar by requiring a case to go to debate (i.e. legal argument) on a point of law without evidence. In the Court of Session, this is known as a “procedure roll” hearing.

6.3 Abuse of process

Third, the concept of “abuse of process” was until recently not recognised in Scottish procedure but has now been adopted, with essentially the same principles applying as in England. A 2012 speech by Lord Reed, a Scottish judge who is now the President of the UK Supreme Court, describes the history of this. In 2004, Lord Gill suggested that the concept could extend to a claim obviously without merit which wastefully occupied court resources, but I can find little trace of that notion being applied subsequently.

6.4 Proof before answer

Fourth, the Scottish court can order something analogous to the English trial of a preliminary issue. This is known as a proof before answer (a “proof” in Scotland is the equivalent to a “trial” in England and Wales).

6.5 Summary diligence

Fifth, the Scottish registration procedure of summary diligence, mentioned earlier on in this article, still exists, though it only applies to certain kinds of debt and requires the debtor’s prior consent, as summarised here.

7. Conclusions

It’s impossible to describe the reality of such a topic by principles alone. The reality is in the practical implementation.

I’ve not been able to attempt any statistical analysis of how the shortcuts discussed in this article have been applied. Researching that would be challenging, as many if not most decisions are not published and even where they are available, it is hard to compare them accurately given that the narrative in a judicial decision – the facts and points which are included or emphasised, and how they are characterised – is likely to be coloured by the conclusion.

However, my overwhelming sense, based on my own time in practice (some years ago now) in England, and based on what I’ve read and heard about it since, is that such shortcuts continue to have potential both for effectiveness and self-destructiveness when the relevant principles are applied by determined and imaginative parties and practitioners. Jonathan Lowe makes some important points in the text I’ve quoted at 5.1 above.

But the fact that such shortcuts continue to be attractive should give food for thought as to the continuing problems of the standard, non-shortcut litigation process.

And while reform to limit the oppressiveness of SLAPPs is welcome, perhaps the evident strength of the case for doing so in that context might also invite reflection on the oppressiveness of much litigation more generally, particularly in cases where one party has significantly more resource to throw at the matter.

Perhaps at some point, the “heretical” (soi-disant) 2017 observations of the then-President of the Supreme Court (Lord Neuberger) will be taken more seriously, calling into question the biggest source of expense in English procedure:

It seemed to me that the value of the expensive and well-established practices of disclosure of documents and of cross-examination of witnesses was highly questionable.

It’s really quite something when the top judge in a system questions the utility of its most fundamental characteristics. There have been some recent reforms to disclosure in E&W, intended to make it more focused – the impact remains to be seen, but I have my doubts. Other recent reforms – relating to witness statements – were more about attempting to improve their quality, not questioning their utility in the manner of Lord Neuberger.

Although there are some other reforms in the pipeline intended to make the litigation systems in both jurisdictions more suitable for cases of moderate value (e.g. in E&W, fixed recoverable costs, online dispute resolution), it seems likely that, as a whole, they are likely to remain largely unchanged in the near future, with the parties being left to find their own way, by shortcuts of the type discussed in this article, by agreed settlement (mediated or not), by abandonment of claims or surrender of defences, by contracting-out (e.g. arbitration), by special exception (e.g. for SLAPPS) or otherwise.

If you will forgive the cliché, it seems that culture eats rules for breakfast